Note: this is part one of an as-yet unknown number of informal articles I’ll be posting here related to the dynamics of human-machine teams, including how these dynamics are informed by the degree of trust between teammates.

The wave of generative AI products and services that has swept the AI landscape and the popular consciousness in 2023 has done so for two reasons. The first is that this has been the most publicly engrossing, and some might say visceral, evidence that advancements in automation are beginning to encroach on domains like creativity, insight, and other characteristics that were previously characteristic of only natural intelligence (r.i.p. Turing test). The second is that generative AI offers clear and diverse paths to improving or enhancing human capabilities, enabling users to be somehow ‘more’ than they otherwise could be. Now a novice coder can generate a working application prototype with the help of code Llama or Github co-pilot in hours or days instead of weeks or months, just as tools like Midjourney and ChatGPT can allow teams to churn out dozens of ideas for marketing copy, website content, presentations, et cetera, allowing them to iterate quickly towards a desired end result. This promise of somehow improving the outcome, efficiency, safety, et cetera of human endeavors through the application of automation did not begin with generative AI, however: this is just the most recent and extremely visible example of the decades-old concept of human-machine teaming (HMT).

Some machines are better teammates than others

Human-machine teaming is, simply put, the collaboration of one or more humans with one or more machines on some goal-directed task or tasks.

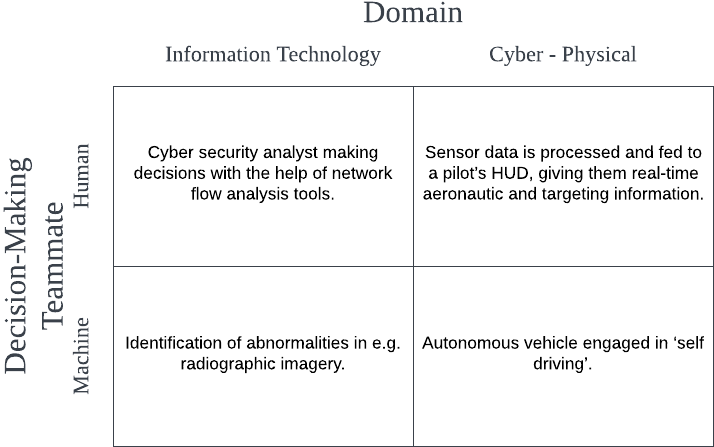

Paradigms in HMT can be broken out along several dimensions, including whether the team will be operating purely as an information system or a cyber-physical system (CPS), as well as the channel through which the HMT is able to interact with the world. In the table below, I present some examples of how different HMTs can be considered in this framework:

Table 1: A framework to consider HMTs based on the domain in which they are intended to act and the member of the team which is ultimately responsible for making a decision.

An HMT is inherently a meta-system which is comprised of human and non-human agents with varying degrees of complexity underlying their decision-making processes, as well as the interrelationships that exist between members of the HMT. Crucially, it must be remembered that the state of an HMT might evolve an a function of time, as the decision-making processes or, if appropriate, the physical capabilities of any of its members is altered or if relationships between members of the team change (e.g. a human may rely more on its machine teammates temporarily if its cognitive and / or physiological properties are altered due to the time criticality of making an accurate decision).

Why HMTs?

A core part of being a human decision-maker over the previous few millennia has been accepting - to a certain extent - and seeking to address shortcomings in our ability to make the best decisions possible based on the most complete and accurate information possible. For the vast majority of this time, this approach involved extending the human umwelt with the help of other animals such as dogs and pigs for olfaction-based detection and classification, as well generally using other animals to aid our decision-making processes such as placing canaries in coal mines to inform humans of degenerating air quality. This use of assistive agents to augment human sensation naturally evolved to encompass more analytical tasks as advancements in computer science gave rise to machines which can, in some circumstances, perform analytical tasks. However, the analytical tasks which the present generation of machines excels at are still largely complementary to humans’ competencies.

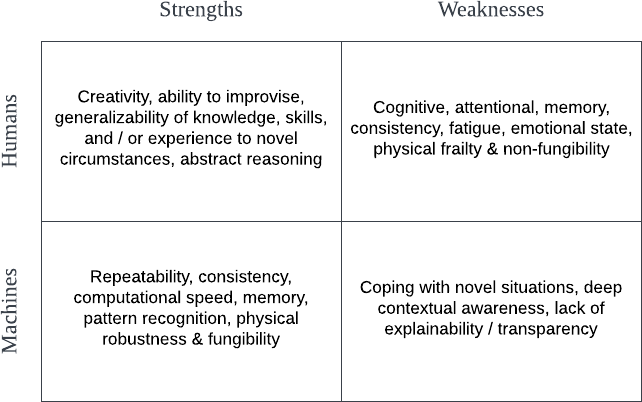

****Table 2: HMTs leverage the complementary strengths of their human and non-human components.****

What this table illustrates is that the promise of HMTs is to, in a domain or application-specific manner, pair teammates with complementary skillsets such that a shortcoming in the attributes of one team member does not imperil an operational objective. For example, cognitively speaking, humans excel at abstract reasoning under novel and uncertain conditions, whereas machines can much better cope with high-dimensional and / or high-throughput data analysis. Therefore, a machine teammate is well-suited to identifying threatening traffic patterns in network flow data, and the human is well-suited to taking that information and applying it by taking some corrective action or informing relevant stakeholders.

Dynamics at Play

As mentioned previously, the HMT is comprised of both the teammates themselves, as well as the relationships between the teammates, which may evolve over time. Ultimately, the performance of a HMT depends on all team members performing appropriately in their roles and being utilized the the extent that best improves the performance of the team. Therefore, you can consider the performance space to be the space of possible outcomes of the HMT as measured by situation-specific metrics, and the evolution of this performance space to be a function of numerous factors relating to the performance of the teammates as individuals and the degree to which the teammates perform cohesively with the other members of the team. Defining these dynamics will be the purpose of the next installments in this series, coming up next!